Up and Down with Compur

The development and photo-historical meaning of leaf shutters

by

Klaus-Eckard Riess

translated

by Robert Stoddard

When it first appeared, the photographic camera already consisted of three indispensable components: The photo-sensitive layer, the image-forming objective or lens, and the shutter, which regulates the exposure time. Shutters can be divided into two main types:

- The focal-plane shutters, in which a slit or opening moves across the optical axis to make the exposure, the slit being formed between two curtains of rubberized material or of metal usually positioned very near the focal plane;

- The leaf shutters, in which a wreath or ring of sectors opens around the optical axis.

Both shutter types have their advantages and disadvantages. The title of this article easily can arouse the impression that Friedrich Deckel’s Compur shutter carries the blame for the

downfall of the German photo industry. But only a portion of the responsibility comes from this source. The greater problem was the German camera industry itself, which focused its attention for much too long a time on the advantages of the leaf shutter, and reacted only slowly when the limited possibilities were revealed and the Japanese had introduced innovative cameras with fully interchangeable objectives onto the market.

If one begins with the “Adam and Eve” of camera history, then one can probably say that the small movable flap before the objective of the Daguerre camera represents the first camera shutter from the year 1839.

In the following decades one got along without an actual shutter. It was sufficient to remove, and after some minutes-long exposure, replace the lens cap. Only as dry plates coated with a more photo-sensitive emulsion appeared, did the need for a more exact control of the exposure times arise After 1880 an enormous amount of more or less well-thought-out shutter constructions appeared on the market. Most were pneumatically released by squeezing a rubber bulb. They were sometimes positioned behind the objective, or at the completely correct place, in the optical center between the lenses that comprised the objective. Different types of so-called Guillotine or drop-board shutters became forerunners of the focal-plane shutter, e.g., the E. Brandt & Wild moment shutter of 1881.

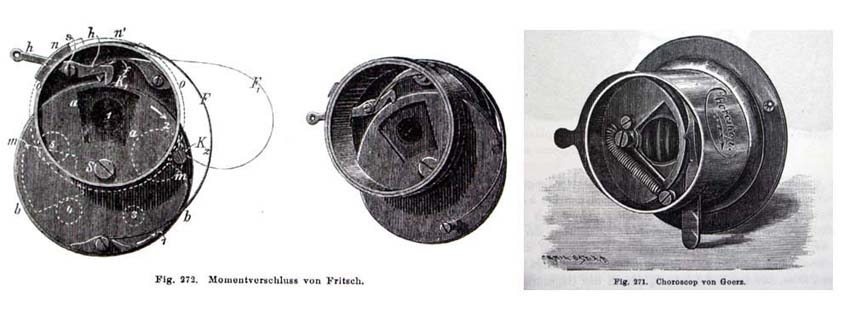

One of the first slit shutters which was correctly positioned directly before the focal plane, was patented by Ottomar Anschütz in 1888. One is reminded of the rotary shutter of the Robot camera when one sees the construction of K. Fritsch in Vienna (1890), in which a round disk provided with an opening turns in the path of rays from the objective. The moment shutter of C. P. Goerz’s “Choroscop” objective (Berlin, 1892) functions in a similar

way.

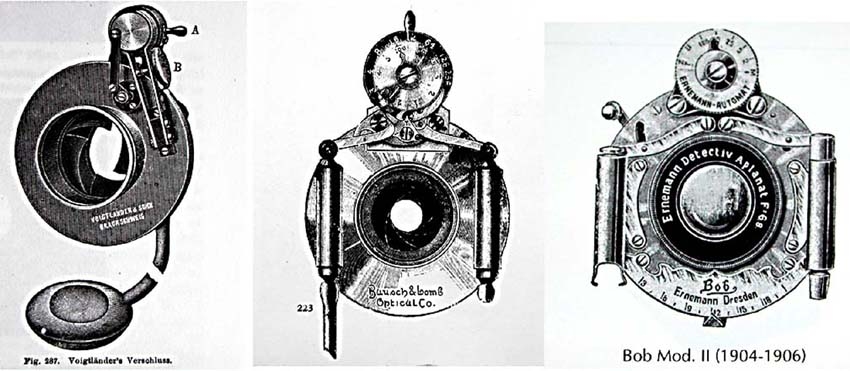

In 1890, Voigtländer brought to market a correctly designed, pneumatically released leaf shutter with 4 sectors. The most popular leaf shutter toward the end of the 19th century was the “Unicum” of Bausch & Lomb in Rochester. It became the model for many others, like the Bob Mod. II of Heinrich Ernemann in Dresden. Ernemann manufactured many leaf shutters, until 1926 when the company was merged into Zeiss Ikon AG and had to stop shutter production.

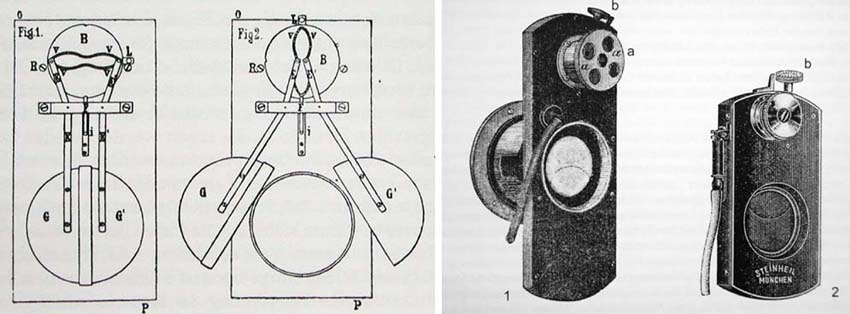

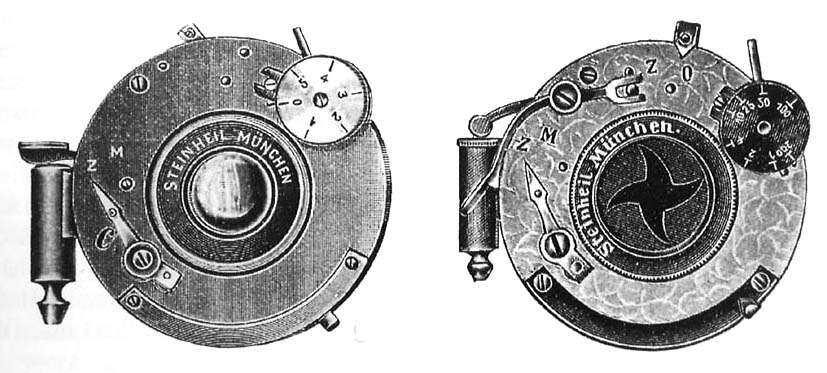

Since we want to follow the development of those leaf shutters which had an influence in the camera industry into the seventies, we must turn our gaze to Munich. Here the company Steinheil manufactured relatively fast lenses, which made precise control of exposure time necessary, especially in combination with the new, more sensitive dry plates. Already in 1881 Steinheil patented a shutter, in which two half-moon-shaped plates

swung out to the sides. Owing to the opposite movements executed by the closing shutter blades, the risk of blurring was smaller than with the drop board shutters. Steinheil’s “Universal Objective Shutter”, which Carl Pritschow had designed in 1888 was also generally recognized in this time period. This shutter was also virtually vibration-free, because the two thin closing blades of metal moved in opposite directions. The shortest exposure time of the Steinheil Pritschow shutter was 1/200 second.

Steinheil leaf shutter 1881 Universal Objective Shutter by Carl Pritschow 1888

Since 1882, a certain Christian Bruns worked for Steinheil. In 1899 he built the first correct Steinheil leaf shutter with 4 blades, and in 1902, the “Universal Automatic Shutter Model C” followed. The adjustment of the exposure times from 1 sec. to 1/200 second took place with this shutter with the help of a leather brake.

In the research division of the Steinheil company a mechanic was employed who had worked before for Ernst Abbe in Jena. This young man was named Friedrich Deckel. In 1898

he created his own mechanical workshop, and in 1903 Christian Bruns joined him there. The result of their co-operation was the Compound shutter in the year 1905, in which the shutter times were controlled by an airbrake, i.e., a cylinder with a piston. The Compound shutters were in production for 65 years, the last being supplied in 1970.

For reasons that are unknown today, Christian Bruns withdrew from the co-operation, but without giving up his work with shutters. In 1910 he applied for a patent on a shutter in which the exposure times were regulated by means of a mechanical retarding mechanism. At Carl Zeiss, the significance of this invention was recognized and the patent was acquired in order to place it at the disposal of Friedrich Deckel. This shutter was baptized with the name “Compur”, a fusion of “Com pound” and “Uhr werk”, the German for “clockwork” in reference to the retarding mechanism.

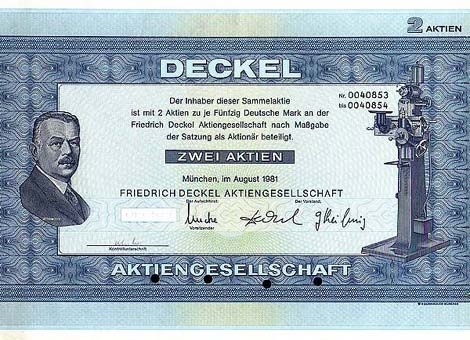

At this time Carl Zeiss already possessed a 16.8% portion of the Friedrich Deckel GmbH firm. Although the name Deckel since then has always been synonymous with Compur, it was not Friedrich Deckel but Christian Bruns who designed the first of these shutters. Since the machine tools available on the market did not correspond to the quality requirements of Friedrich Deckel, he designed his own machines. This machine production became the second leg of Friedrich Deckel GmbH. Deckel milling machines since then have always enjoyed a good reputation with all machine shops.

Later Deckel share with the portait of Friedrich Deckel and a milling machine

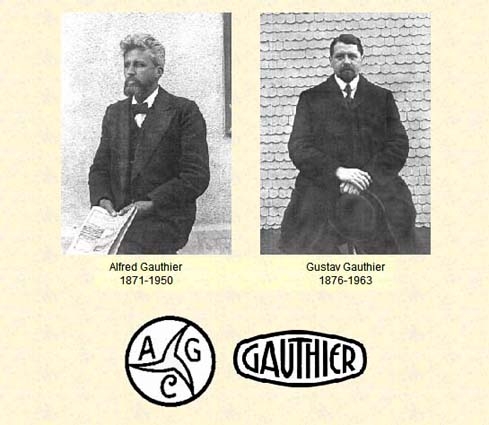

Friedrich Deckel undertook nothing without first consulting Carl Zeiss. Agreements did exist about working co-operations, about price strategy and about supplies to competitive companies. A secret community of interest, including not only Carl Zeiss and Friedrich Deckel but also Alfred Gauthier in Calmbach and Bausch & Lomb in Rochester was formed. At the latter company Zeiss possessed 25% of the shares. Since 1910, Carl Zeiss had also owned a portion of Alfred Gauthier GmbH, which would later develop into the largest shutter factory in the world. By 1931 Carl Zeiss had acquired a majority of the Gauthier stock, but this fact was kept secret so that Gauthier could supply shutters to Zeiss’ competitors.

The brothers Alfred and Gustav Gauthier had created their mechanical workshop in 1902 at Calmbach in the northern Black Forest. In 1904 they began the production of Koilos shutters, regulated at first by a leather brake, and later by a pneumatic retarding mechanism. Leaf shutters with the designations Derval, Ibso, Singlo, Telma, Ibsor, Vario and Pronto followed. The latter name originates from latin and means “ready”. In 1935 was added the shutter named Prontor, which later became a famous registered trade mark

and then the name of the entire company.

Alfred Gauthier manufactured quality shutters, which however never reached the standard and the prestige of Compur. The Gauthier shutters were built into the cheaper types of camera, a matter that was contractually fixed. Just as with Deckel, Gauthier also manufactured its own machine tools. It is no coincidence that Carl Zeiss straightaway in 1910, i.e., only one year after the fusion of some camera factories with Ica AG, acquired portions of both Friedrich Deckel and Alfred Gauthier, and thus secured control over the two most substantial shutter manufacturers. The advantage was mutual. Carl Zeiss ensured its objective production and at the same time shutter production by Deckel and

Gauthier was also ensured. History repeated itself in 1926 with the merger of companies to form Zeiss Ikon AG. Heinrich Ernemann, one of the merged companies, had to give up its shutter production and Zeiss Ikon obligated itself to build Compur shutters into 80% of their cameras.

In 1927 the small speed-setting dial of the Compur shutter was replaced by a large ring. In 1928 the Compur S with self-timing automatic shutter release was introduced, and in 1934 the Compur Rapid with a shortest exposure time of 1/500 second appeared.

In 1925 Ernst Leitz of Wetzlar created a sensation when it began to market Oskar Barnack’s small Leica camera for 35mm motion picture film. Zeiss Ikon AG tried to keep up with the small format trend, e.g., in the 3x4cm roll film format with the small “Kolibri” camera, which was equipped either with a Tessar objective and a Compur shutter, or in the cheaper version with a Novar objective and a Telma shutter. Naturally the Kolibri could not match the features and possibilities which the Leica had to offer. The young engineer Heinz Küppenbender was brought from Carl Zeiss Jena to Dresden. In co-operation with Zeiss Ikon’s general manager Emanuel Goldberg he had to construct a system camera that would outperform the Leica without infringing Leitz patents. As is known, the Contax was the result of these efforts. The Friedrich Deckel firm in Munich learned of the nature of the Contax shutter development and, claiming that it contravened the agreements that they had with Zeiss Ikon AG, protested vehemently. On 25 November 1933, Deckel wrote the managing director of Carl Zeiss, Paul Henrichs:

“Zeiss Ikon equips ever more models with focal-plane shutters, which for me is in the end just as unfavorable as if it would equip these cameras with another make of leaf shutters, because the business is to me effectively lost. In addition, through these measures, more and more propaganda is made for the focal plane shutter, which must also have an unfavorable effect for my shutter production. A really friendly co-operation can take place nevertheless, but only if more consideration for my company is taken in this matter in Dresden.”

An answer of Carl Zeiss to this song of complaint is not known. But as we know, Friedrich Deckel could not prevent Zeiss Ikon from equipping its prominent camera models Contax, Super Nettel, Nettax and the Contaflex twin-lens reflex with the new metal focal-plane

shutter. Today it may surprise us that Friedrich Deckel was not asked to develop and supply a metal focal-plane shutter. The technical designers in Deckel’s company must have possessed the technical prowess for such a task.

On 1 September 1939, World War II broke out. Shutter production went on low flame and Friedrich Deckel GmbH had to change its production facilities to produce fuel pumps for BMW aircraft engines. Also with Alfred Gauthier in Calmbach, arms production stepped into the foreground.

In 1945, with the war over, both companies began a modest new start making shutter models from the prewar period. The newly founded Zeiss Opton in Oberkochen undertook

the old business relations to Deckel and Gauthier. Soon these firms were producing shutters that bore new designations such as Synchro-Compur and Prontor SV, because they were synchronized and thus followed the developments in flash technology.

Advertisements in “Photo-Technik und -Wirtschaft” in May 1952

During the first two postwar decades, Deckel and Gauthier reported great successes with their Compur and Prontor shutters. The leaf shutter has many advantages. First of all it runs practically vibration-free, and secondly it exposes the entire image field simultaneously, making flash photographs possible even with the shortest exposure times. No focal-plane shutter can match this feature, because the moving slit of such shutters typically exposes only a portion of the image at a time. With a leaf shutter camera the photographer could thus combine the available lighting better with the light from a flash, for example using the flash to lighten the shadows in a sunlit picture. This feature of the leaf shutter also contributed at that time to the popularity of the Hasselblad 500C.

Leaf shutters could be mass-produced and adapted to all possible cameras. That was naturally an advantage for the many camera factories which sprang up in the post-war period in Germany. The fact that the relatively small opening diameter of the leaf shutter considerably limits the possibility of interchangeable objectives played no major role at first.

In this area the focal-plane shutter shows a great superiority, but it has a few substantial disadvantages. Primarily, flash synchronization is problematic, because the focal-plane shutter exposes the whole image field simultaneously only when the longer exposure times are selected. Shorter exposure times than 1/25 or 1/50 sec. could not be used with the focal-plane shutter cameras of the fifties for photography with electronic flash. Another

disadvantage of the focal-plane shutter is that it produces distortion of objects photographed in motion. E.g., a moving car produces an image that is unnaturally longer or shorter than reality, depending on whether the shutter curtains move in the same or opposite direction from the motion of the car. Similarly, the shape of a rolling wheel is distorted from round to elliptical.

There were thus plentiful reasons to give leaf shutters the priority.

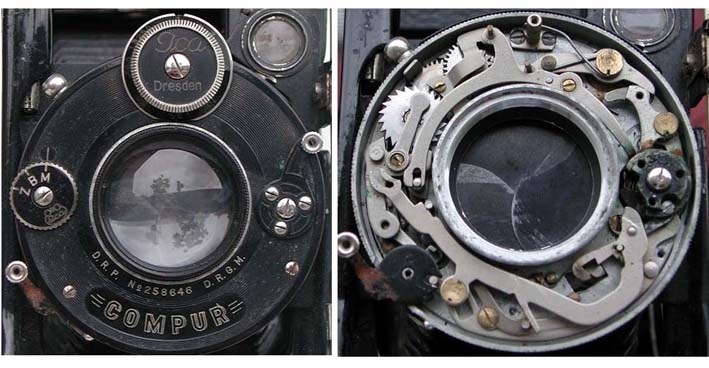

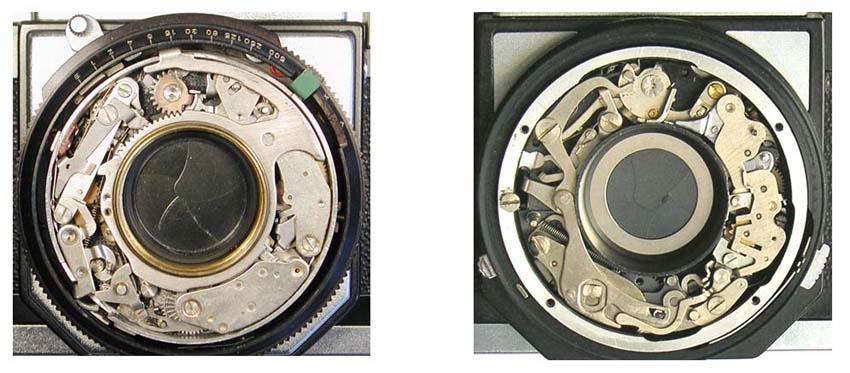

Synchro-Compur of the Contaflex I Prontor-Reflex of the Contaflex beta

In 1953 Zeiss Ikon AG in Stuttgart offered the epoch-making Contaflex. It was introduced with the claim to be the world’s first miniature-format mirror reflex camera with a leaf shutter. The chief designer Edgar Sauer had succeeded in coordinating the movements

of the mirror, a focal-plane baffle plate, and the leaf shutter. For viewing and focusing, the leaf shutter stood completely open, with the mirror in viewing position and the film shielded from fogging by the baffle plate. When the shutter release was pressed, the shutter first closed, then the baffle plate uncovered the film plane while the mirror rose out of the light path, and finally the shutter opened and closed, making the exposure. From the time the shutter release was pressed up to the opening of the shutter for the start of the exposure took only about 20 milliseconds. Although the first Contaflex had a fixed objective lens, the following models were all equipped with objectives with interchangeable front components, such that by exchange of

the front lens component different focal lengths could be selected even though

the rear component of the objective remained fixed in place.

Most of the substantial camera manufacturers followed the trend to mirror reflex cameras with leaf shutters:

Kodak Retina Reflex (1956), Voigtländer Bessamatic (1958), Braun Paxette Reflex (1958), Agfa Ambi Reflex (1959), Wirgin Edixa Elektronica (1962). Deckel and Gauthier offered the appropriate, further-developed shutters for these cameras, e.g., with light value scales,

depth of field indicators, and interchangeable mounts for objectives or components.

Advertisement in “Photo-Technik und -Wirtschaft” 1956

At the 1956 Photokina show, the drum was being beaten for the compact eyelevel viewfinder cameras with interchangeable objectives, many with coupled rangefinders. To name a few of them: Kodak Retina, Zeiss Ikon Contina III, Agfa Ambi Silette, King Regula IIId, Futura, Diax, Leidolf Lordomat, Braun Paxette, and Voigtländer Vitessa T.

Some viewfinder cameras with interchangable lenses, 1956

In 1950 Voigtländer had already brought the 35mm Prominent on the market in an attempt to compete with the Leica and Contax. The Prominent was the world’s first rangefinder camera with leaf shutter and interchangeable objectives (after all Zeiss Ikon Tenax II 24×24 mm 1938, AkA Akarette 1948).

Between 1957 and 1960 leaf shutter production boomed. Gauthier’s Prontor works in Calmbach employed 3250 workers and had a daily output of 10.000 shutters. Deckel’s Compur works in Munich employed at the same time about 1500 people.

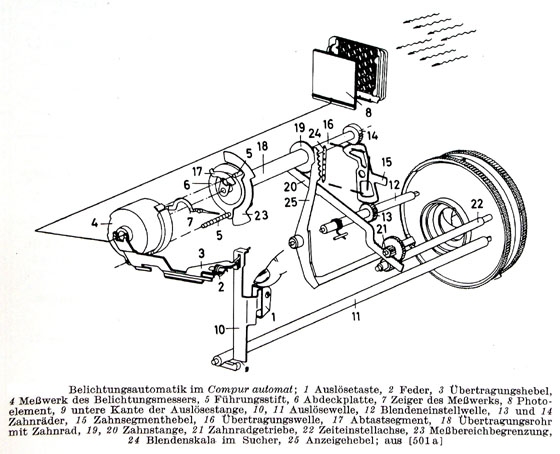

In 1959 the Agfa Optima opened the era of the fully automatic camera, soon to be offered by virtually all the manufacturers. The exposure mechanism of these cameras was actually

quite mechanical, and involved letting the exposure meter respond to the light level present in the scene, clamping the needle in position, and then mechanically sensing the needle position as a data input to the exposure mechanism.

Most manufacturers availed themselves of the three shutter types, which Gauthier manufactured for this purpose:

- Prontor-Lux was the simplest, used e.g. in the Adox Polomatic II and the Dacora 4D. For each film speed set into the shutter, a corresponding shutter speed was set, such that e.g., all films having a speed of 18 DIN were exposed at 1/30 sec. and all films having a speed of 27 DIN were exposed at 1/500 second. The exposure mechanism then selected only the appropriate aperture.

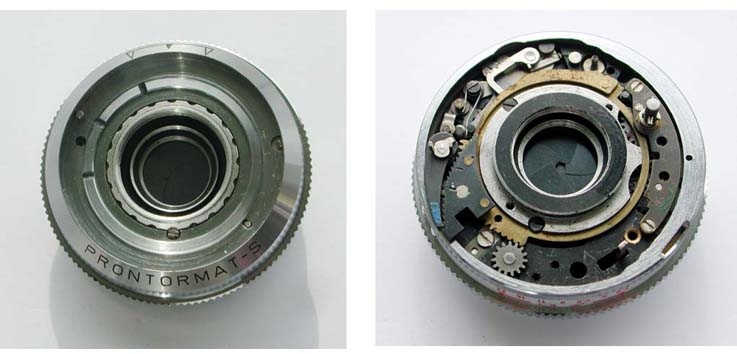

- The Prontormat-S was probably the most-used shutter, e.g., in the Zeiss Ikon Tenax or in the Voigtländer Dynamatic I. Two connected curves were coupled with the exposure mechanism and adjusted according to a fixed shutter-speed/aperture program.

- The Prontormatic was intended to be used in cameras for those creative amateurs who wanted to select the shutter speed and let the exposure meter produce the correct aperture, as e.g., with the Adox Polomatic III S or the Voigtländer Dynamatic II.

Also Friedrich Deckel manufactured a Compur Automat for this so-called simplex control. The Compur Automat was used e.g., with the Super Baldamatic and with the Retina Automatic II and III.

The trend to automatic exposure mechanisms appeared among the SLR cameras also. In 1959 the French Savoyflex appeared, with a Prontor reflex shutter providing shutter speed preselection and automatic aperture control mechanism. In 1961 came Voigtländer’s Ultramatic and in 1962 Zeiss Ikon’s Contaflex Super B came on the market, both with Compur shutter. The Ultramatic offered even rapid mirror return. Everything was of outstanding quality, but mechanically complicated, expensive to manufacture, and difficult to repair. In addition, the small opening diameter of the leaf shutter prevented the designing of a full range of high-speed interchangeable objectives.

Contaflex S with Synchro-Compur-X autoexposure mechanism with shutterspeed preselection, internal metering, automatic flash mechanism, and interchangeable Tessar front component. 1968

The fact that the Japanese cameras emerging in these years were increasingly innovative and cheaper, but in addition of good quality, was arrogantly overlooked by the German camera manufacturers. Whether the leadership of Carl Zeiss in Oberkochen, who had purchased in 1958 for a large sum of money the Deckel Compur works, influenced other manufacturers to cling to the leaf shutter concept I do not know. It is generally known, however, that the Zeiss boss Heinz Küppenbender forbade the development

of advanced SLR designs at the Voigtländer firm, which had been acquired in

1956 by Carl Zeiss.

When they tried to respond to the Japanese challenge with the 1966 introduction of the Icarex, it was much too late. The Zeiss Ikon/Voigtländer group alone produced cameras with 5 different objective mounts, a complexity which made their products uncompetitive. In 1971 the leadership at Carl Zeiss with a heavy heart resolved to end camera production at Zeiss Ikon in Stuttgart and at Voigtländer in Braunschweig. Eventually other camera manufacturers got into financial difficulties and had to end camera production:

e.g.,

Aka in Friedrichshafen 1960, Adox in Wiesbaden 1965, Leidolf at Wetzlar 1965, Braun at

Nuremberg 1968, Dacora at Reutlingen 1972, Wirgin at Wiesbaden 1973. Kodak in Stuttgart stopped the production of 35mm cameras in 1967.

Naturally, this negative development did not leave Deckel and Gauthier untouched. In 1965 Alfred Gauthier’s Prontor Works had already begun a reduction of staff, until in 1975 only 740 people were remaining. In the Compur works in Munich, concentration on other products started in 1972. By 1976 the remainder of Compur shutter production was moved into the Prontor works in Calmbach. There production continued, e.g., with shutters for Hasselblad and for large format cameras. Also electronic shutters were developed. The heyday of West German camera production was, however, once and for all past.

It is worth while to cast a look on the other side of the iron curtain. While the leading West German camera factories Leitz, Zeiss Ikon and Voigtländer clung for the time being to the

rangefinder concept, the photo industry in Dresden led the way to the mirror reflex concept with focal-plane shutter, which had begun with the Kine Exakta and the Praktiflex in Dresden. Camera names such as Exakta Varex, Contax S, Praktica and Praktina wrote history. In time, the Praktica received the highest priority. At a time when the majority of

the West German camera industry was already on its last legs, the Dresdners offered the innovative L and B-series of their Praktica, and produced them in enormous quantities. Other amateur models and viewfinder cameras needed leaf shutters. Some camera types, probably above all for the export market, were equipped with Compur shutters made by Deckel in the West.

In the long run, however, East German manufacturers did not want to be dependent on this source. Therefore, during the fifties, they developed their own leaf shutters with names such as Cludor, Vebur, Tempor and Prestor. With the Prestor Rapid shutter, a shortest exposure time of 1/750 second was achieved.

Altix V with Tempor shutter

The success of the Contaflex and other mirror reflex cameras in the west, especially due to the advantage of these models in flash photography, had tempted the Dresdners to the development of a similar camera. This was the Pentina with its futuristic styling, with Prestor leaf shutter and with interchangeable objectives from Carl Zeiss Jena. Fortunately it was recognized soon that with this camera, the Dresdners were on the wrong track. Therefore the Pentina remained the only camera of this kind from Dresden. It was manufactured only from 1961 to 1965.

Nikon by the way paid for a similar lesson with the mostly unsuccessful Nikkorex Auto 35 in 1964. Only in Oberkochen and Stuttgart the penny seemed to fall somewhat more slowly.

Two leaf-shutter cameras from the DDR:

Werra with Synchro-Compur Pentina with Prestor

With the collapse of the GDR regime in 1989, the East German camera production also approached its final hour. A completely unrealistic relationship between production costs and profit led to the liquidation of Dresden’s photo industry during a long and painful process. But neither Compur nor Prontor had any part in this. And how does it look today with the two famous shutter names? In Munich the Compur Monitor company still exists, which traces its roots back to Friedrich Deckel. But it produces measuring instruments for the gas industry instead of shutters. Also at the company Prontor GmbH in Calmbach there

is vibrant active life, however mainly in the area of medical technology. The history of the dilemma of the German photo industry 40 years ago shows us how arrogance, lack of adaptive ability and wrong decisions can lead to the fall of a whole industry.

“Pride

comes before the

Fall” from the proverbs of Solomon. But we can talk, and everyone can play the know-it-all!